Pregnancy SmartSiteTM

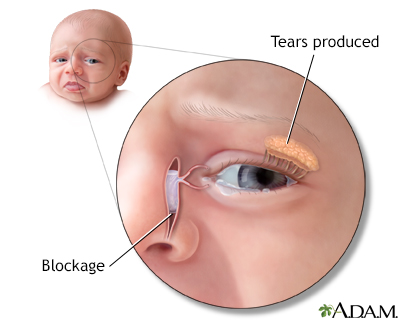

Dacryostenosis; Blocked nasolacrimal duct; Nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) DefinitionA blocked tear duct is a partial or complete blockage in the pathway that carries tears from the surface of the eye into the nose. CausesTears are constantly being made to help protect the surface of your eye. They drain into a very small opening (punctum) in the corner of your eye, near your nose. This opening is the entrance to the nasolacrimal duct. If this duct is blocked, the tears will build up and overflow onto the cheek. This occurs even when you are not crying. In children, the duct may not be completely developed at birth. It may be closed or covered by a thin film, which causes a partial blockage. In adults, the duct can be damaged by an infection, injury, or a tumor. SymptomsThe main symptom is increased tearing (epiphora), which causes tears to overflow onto the face or cheek. In babies, this tearing becomes noticeable during the first 2 to 3 weeks after birth. Sometimes, the tears may appear to be thicker. The tears may dry and become crusty. If there is pus in the eyes or the eyelids get stuck together, your baby may have an eye infection called conjunctivitis. Exams and TestsMost of the time, the health care provider will not need to do any tests. Tests that may be done include:

TreatmentCarefully clean the eyelids using a warm, wet washcloth if tears build up and leave crusts. For infants, you may try gently massaging the area 2 to 3 times a day. Using a clean finger, rub the area from the inside corner of the eye toward the nose. This may help to open the tear duct. Most of the time, the tear duct will open on its own by the time the infant is 1 year old. If this does not happen, probing may be necessary. This procedure is most often done using general anesthesia, so the child will be asleep and pain-free. It is almost always successful. In adults, the cause of the blockage must be treated. This may re-open the duct if there is not too much damage. Surgery using tiny tubes or stents to open the passageway may be needed to restore normal tear drainage. Outlook (Prognosis)For infants, a blocked tear duct will most often go away on its own before the child is 1 year old. If not, the outcome is still likely to be good with probing. In adults, the outlook for a blocked tear duct varies, depending on the cause and how long the blockage has been present. Possible ComplicationsTear duct blockage may lead to an infection (dacryocystitis) in part of the nasolacrimal duct called the lacrimal sac. Most often, there is a bump on the side of the nose right next to the corner of the eye. Treatment for this often requires oral antibiotics. Sometimes, the sac needs to be surgically drained. Tear duct blockage can also increase the chance of other infections, such as conjunctivitis. When to Contact a Medical ProfessionalSee your provider if you have tear overflow onto the cheek. Earlier treatment is more successful. In the case of a tumor, early treatment may be life-saving. PreventionMany cases cannot be prevented. Proper treatment of nasal infections and conjunctivitis may reduce the risk of having a blocked tear duct. Using protective eyewear may help prevent a blockage caused by injury. ReferencesHurwitz JJ, Olver JM, Dutton JJ. The lacrimal drainage system. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 12.12. Olitsky SE, Marsh JD. Disorders of the lacrimal system. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 665. | |

| |

Review Date: 7/16/2024 Reviewed By: Neil K. Kaneshiro, MD, MHA, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. No warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability, timeliness, or correctness of any translations made by a third-party service of the information provided herein into any other language. © 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited. | |

Blocked tear duct

Blocked tear duct